Ocular Implants for Drug Delivery: Improving Patient Outcomes

Table of Contents

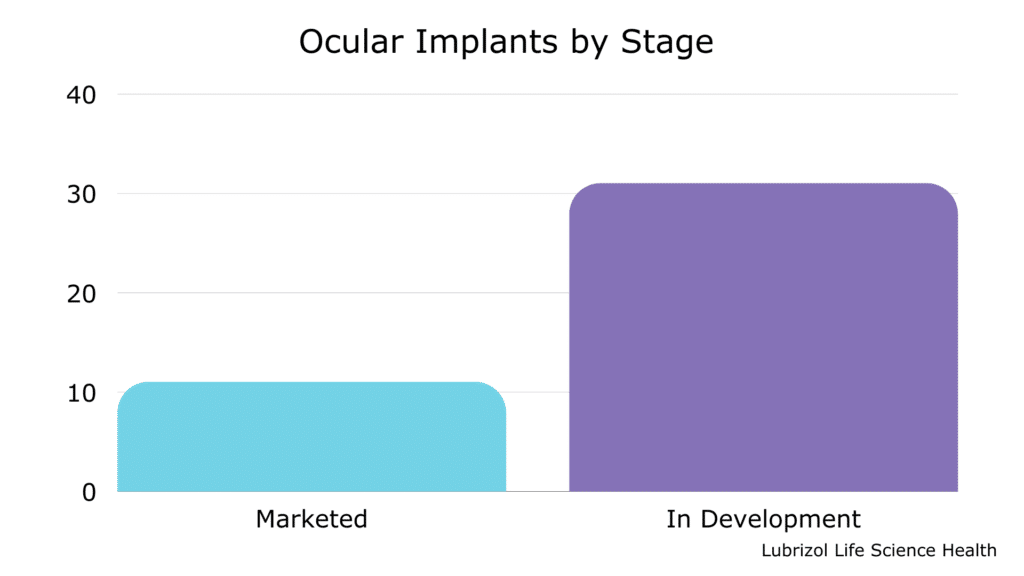

Did you know that there are already 11 ocular implants on the market and over 30 in development? (See Table 1 and Figure 2)

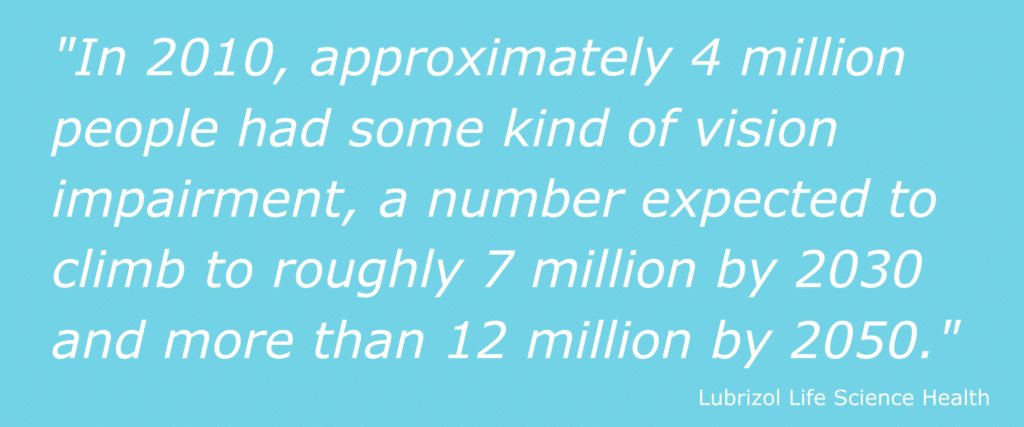

Every year, more and more people live with eye disease or vision impairment of some kind, requiring treatment to avoid additional vision loss or blindness.

In 2010, approximately 4 million people had some kind of vision impairment, a number expected to climb to roughly 7 million by 2030 and more than 12 million by 2050. Cases of macular degeneration alone — which grew 18% from 2000 to 2010 — are expected to more than double by 2050.¹

That growth, spurred in part by an aging population, creates new demand and opportunities in the ocular pharmaceutical space.

Ocular implants — small devices designed to be inserted into the eye and deliver a drug locally over an extended period — are rapidly gaining ground as a treatment option. As patients continue to seek out convenient, less invasive treatments, the demand for these implants will continue to increase.

The Current State of Ophthalmic Drug Delivery

Generally, ocular drug delivery falls into one of two categories: anterior and posterior.

Anterior drug delivery methods are most often topical and include dosage forms such as eye drops and ointments. These medications are applied to the front portion of the eye.

Thanks in large part to their ease of use, anterior delivery treatments make up the majority of widely available ophthalmic treatments. In 2020, more than 62% of revenue from ophthalmic drugs came from topical treatments.² However, they come with significant drawbacks in treating some eye conditions, particularly those that affect the posterior (back) portion of the eye as topicals cannot reach this area.

Posterior drug delivery methods are less common than their anterior counterparts, partly because reaching the back portion of the eye, mainly the retina, can be challenging. Posterior treatment methods include injections or implants into the vitreous or other surrounding tissue toward the back of the eye.

Posterior treatments can be challenging for both drug developers and patients, however. For example, maintaining the appropriate concentration of a drug in the vitreous — the fluid that fills the eye and keeps the retina in place — can be difficult with injections. Additionally, the molecular weight of a drug can influence how it is eliminated by the patient’s system, making formulation design difficult. Furthermore, for patients, the process of receiving injections in the eye can be unpleasant, and the frequency of treatments inconvenient.

All of this makes ocular implants a particularly attractive treatment option for patients, as they offer well-controlled dosing over a longer period of time than injections and can treat retinal disorders.

Types of Ocular Implants

Ocular implants present a unique solution to the challenges of treating posterior eye disorders, and many are already commercially available, including Allergan’s Ozurdex® dexamethasone intravitreal implant and Allergan’s Durysta™ bimatoprost implant, prescribed for a range of posterior eye conditions.

Broadly, ocular implants come in both biodegradable (bioresorbable) and non-biodegradable (biodurable) forms.

- Bioresorbable implants are inserted into the patient’s eye and safely absorbed by the body over time. These implants combine a drug with a polymer — often polylactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA) — which degrades over time, releasing a drug.

- Biodurable implants do not break down over time and may be removed or refilled once the treatment is complete. These implants often encapsulate a pharmaceutical inside a polymer such as ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA), or silicone.

Each type of implant has advantages and disadvantages. Bioresorbable implants eliminate the need for patients to undergo a follow-up procedure, but they may not be suitable for use with all drugs. Biodurable implants can offer longer, more controlled drug release, but they may require patients to undergo a second procedure to remove them.

Overall, however, implants present a significant improvement for patients and require less frequent administration than ocular injections. When treated with an implant, patients who had previously relied on traditional injections could extend their time between treatments by weeks or even months.

Table 1. Ocular Implants Currently in Development

| Product Name | Owner Company | Most Advanced Phase |

| Renexus Implant | Amgen Inc. | Phase 3 |

| Lucentis Implant | Genentech, Inc. | Phase 3 |

| Travoprost-PPDS Implant | Mati Therapeutics, Inc. | Pre-Clinical |

| PolyActiva Timolol Implant | PolyActiva Pty Ltd. | Pre-Clinical |

| Endophthalmitis Preventive Implant | PolyActiva Pty Ltd. | Phase 1 |

| ENV515 Implant | Aerie Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Phase 2 |

| Olopatadine-PPDS Implant | Mati Therapeutics, Inc. | Phase 2 |

| AR-1105 Implant | Aerie Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Phase 2 |

| iDose TR Implant | Glaukos Corp. | Phase 3 |

| IVMED-10 Implant | iVeena Delivery Systems, Inc. | Phase 1 |

| IVMED-20 Implant | iVeena Delivery Systems, Inc. | Phase 2 |

| Antibody Tablet Program, UCL | UCL Business Ltd | Pre-Clinical |

| ENV1305 Implant | Aerie Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Pre-Clinical |

| Sema3A Inhibitor Lead-2, Synovo | Synovo GmbH | Pre-Clinical |

| Latanoprost-PPDS Implant | Mati Therapeutics, Inc. | Phase 2 |

| iStent Supra® | Glaukos Corp. | Approved |

| Nepafenac-PPDS Implant | Mati Therapeutics, Inc. | Phase 2 |

| AR-13503 SR Intravitreal Implant | Aerie Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Phase 1 |

| LB-100 Ophthalmic, LayerBio | LayerBio Inc. | Pre-Clinical |

| Endophthalmitis Treatment Implant | PolyActiva Pty Ltd. | Pre-Clinical |

| Biodegradable Ocular Implant Program, Polyactiva | PolyActiva Pty Ltd. | Pre-Clinical |

| OTX-TIC Ophthalmic Implant | Ocular Therapeutix, Inc. | Phase 1 |

| PA5108 Ocular Implant | PolyActiva Pty Ltd. | Phase 1 |

| Difluprednate-PPDS Implant | Mati Therapeutics, Inc. | Pre-Clinical |

| Cyclosporine-PPDS Implant | Mati Therapeutics, Inc. | Pre-Clinical |

| Cataracts Program, VisusNano | VisusNano Ltd. | Research |

| IBE-814 IVT Implant | Interface Biologics, Inc. | Phase 2 |

| Dexamethasone-PPDS Implant | Mati Therapeutics, Inc. | Pre-Clinical |

| YUTIQ50 Implant | EyePoint Pharmaceuticals, Inc. | Phase 2 |

| IBE-119 Intracameral Implant | Ripple Therapeutics Corp. | Research |

| iDose TREX Implant | Glaukos Corp. | Pre-Clinical |

Considerations When Developing Ocular Implants

The advantages and demand for ocular implants are clear, but developing and producing them requires several types of special expertise. Companies looking to outsource the development or manufacturing of these products are well-advised to partner with an organization experienced with long-acting dosage forms, and in handling every aspect of ocular products, from polymer selection to aseptic manufacturing.

Sterility Assurance

Drug product manufacturers must ensure that an ocular product is sterile as the eye is particularly sensitive to bacteria, pathogens, and other irritants. Terminal sterilization via heat, chemical gas, or irradiation is the preferred means of achieving a sterile product. However, in cases where a drug or formulation component is not amenable to these techniques, aseptic manufacturing is required.

Regardless of sterilization technique, ophthalmic implant developers must have a strategy for achieving a sterile product, including access to the appropriate manufacturing facilities and an understanding of the regulatory requirements around sterility assurance.

Polymer Selection

Whether implants are biodurable or bioresorbable, they rely on pharmaceutical-grade polymers (excipients) to achieve effective sustained release. Implant developers should ensure that polymers can be manufactured according to Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) and pass the appropriate biocompatibility tests.

Implant Manufacturing

Creating implants that are smaller than a grain of rice requires extreme precision throughout development, prototyping, and production. Consistent manufacturing processes are especially important for ocular implants, as even small changes in drug concentration or implant dimensions can result in drastic differences in product performance.

Ocular implants are frequently made via thermal processing methods such as hot melt extrusion or injection molding, which begins with the compounding step. During this process, a drug and polymer melt and blend together in an extruder.

To ensure a homogenous blend, the polymer may require pre-processing, such as milling polymeric pellets into powder form. Equipment for milling and extrusion can be scaled to meet production needs from R&D through manufacturing.

Once the polymer and drug are combined, they pass through an additional extrusion or molding step, in which heat and pressure form the final implant.³ For rod-shaped matrix implants, the drug-polymer blend may pass through an extruder to form a filament before being cut to form the final product. Reliable compounding and precise extrusion/cutting are crucial for products manufactured via extrusion.

To achieve better control over drug release, implant developers may also create core-sheath systems using biodurable polymers and a co-extrusion technique. Co-extrusion involves the simultaneous extrusion of a drug-loaded core surrounded by a rate-controlling polymer membrane. A specially designed extrusion head is fed by two perpendicular extruders – one supplying the core composition and the other supplying the sheath material. By controlling the core and sheath polymers, sheath thickness, and drug loading, implant developers can tune the drug release to specific targets. This technique has been used to manufacture intravaginal rings that deliver precise levels of drug for months at a time, and experienced scientists can control sheath dimensions down to the micron-level.

Some biodurable implants use silicone, which relies on a different set of mixing, molding, and curing steps to achieve a final dosage form (as opposed to the thermal processes described above). Silicone has long served as a reliable material for medical devices and may offer a suitable alternative to extrusion when a drug is sensitive to elevated temperatures. However, other biodurable polymers offer additional benefits, including increased drug loading or more control over drug release.

Whether the desired ocular implant is biodegradable or biodurable, a drug developer must select a partner with knowledge of API-polymer interactions and the correct equipment to develop and manufacture their product in a GMP environment. A manufacturing partner with experience in long-acting and ocular dosage forms can leverage their experience to reduce development cycles and avoid costly errors in scale-up/manufacturing.

Authors: Robert Lee, Ashley Rein, and Nick DiFranco